“If I make a film starring Kitano, it will be Zatoichi. (Akira Kurosawa, quoted in Sugimura, 2003: 96).”(Karatsu)

An ambassador? No, I’m more like a spy (laughs). (Kitano in conversation with Midnight Eye)

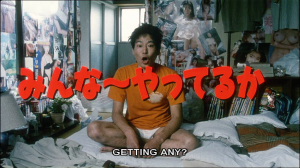

Kitano’s Zatoichi (2003) can be regarded as one of his greatest successes; taking a beloved Japanese propertly, the equivalent of James Bond, and finally having box office success in Japan with this, his tenth film. He has managed to blend his unique sensibilities with a commercial property that is loaded with external parties expectations while preserving many of his filmic eccentricities and bringing comedy to the fore. Kitano managed to please nearly everybody; was a critical darling with the west also. Is Kitano finally finding a home in cinematic Japan rather than just being a strange ambassador to foreign tastes?

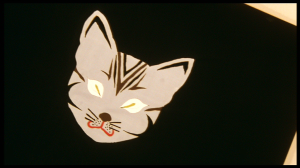

Zatoichi is a remake/reinvention of Japanese film and television icon, Zatoichi, a blind swordsman and masseuse character in one of Japan’s longest TV shows; it ran for 100 episodes, and 26 feature length films. All were played by the same actor Shintaro Katsu, who eventually grew into the director-writer role on the franchise. Kitano takes the established rules of the franchise and brings life to it on an international level.

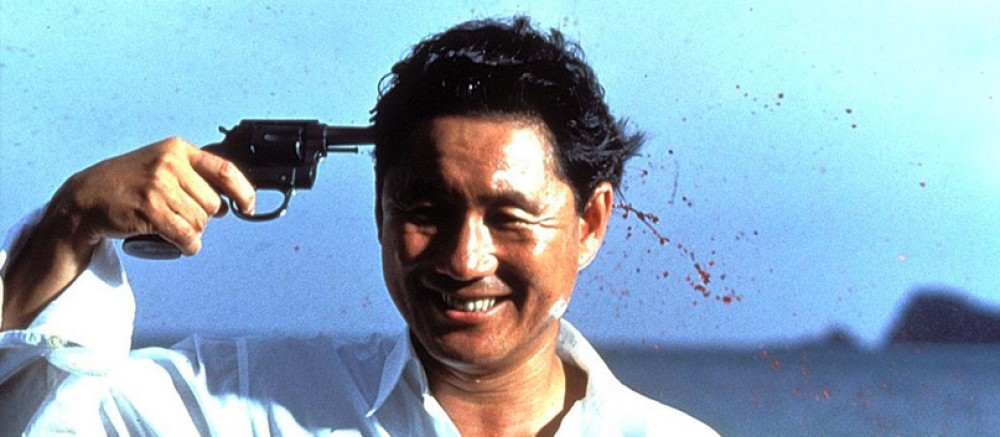

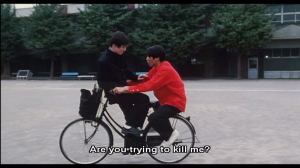

A serious scene is taken down a peg when it is revealed that Zatoichi is wearing make-up.

He takes a genre movie, the historical drama, or jidaigeki, and inserts anachronistic dance sequences, his brand of humour, and gushing fountains of blood to create something new and old. The question is, how much of his trademark touch has he had to give up for the film to succeed? The reception at home that the film had would have you believe that Kitano must’ve ceded to commercial demands on nearly every front. Is Zatoichi a real Kitano film? Has he surrendered to much of his style to suit mainstream audiences? Quite the contrary has happened. He has instead reinforced his style with a film that acts as a commentary between the original property and the films of Akira Kurosawa through the destabilizing use of his original calling, comedy. The original Zatoichi film, takes from Kurosawa’s jidaigeki, though Kenji Misumi foregrounds audience empathy using simple kitsch iconography, damaging their ability to critically interpret the film “ These misused qualities make the audience respond to the film in an uncritical way. Such a relationship between the audience and the film leaves the audience emotionally saturated.” (Karatsu) Misumi’s film fetishises Zatoichi in a variety of ways, to convey some timeless traits that are re used again again, such as closeups of his ears while overhearing nefarious plots.

The original.

“Misumi commercially foregrounded Katsu’s personality. Misumi’s cinematic image disassembles Katsu in order to reconstruct it for the spectator. Presenting Ichi in this way proved to be more enduring than Kurosawa’s creation, Yojimbo, by evolving into a fetishised meta-icon.”(Karatsu) Kurosawa’s films are for more realist in composition that Misumi’s creation of emotion, and use comedy to destabilize the affective nature of the audience relationship to film, and to allow the audience to critically assess the Zatoichi property. “Misumi assembles some kinetic and visceral elements of Kurosawa’s cinematic actions and violence, but he does so to reassure audiences and eradicate difficulty. Kitano’s remake is both parody and homage to the reassuring aesthetics of the original Zatoichi.” (Karatsu) Both Kurosawa and Kitano use humor to destabilize the main characters and their relationships to their identities. His Zatoichi physically falls on his face after defeating the villains, while “. Kikuchiyo’s (The Seven Samurai) restless actions and monkey-like exaggerated giggles and laughter, serve as a contrast to the group-oriented samurai” (Karatsu)

However, Kitano takes these elements of comedy and stretches even further, combining them with anachronistic musical choices. Kitano’s Zatoichi film has strong links to percussive music performances. The villagers can be seen farming in time with non diegetic music on two occasions, and their final sheer spectacle performance featuring all of the good characters, is intercut with Zatoichi on his own, slaughtering the rest of the gang. We cannot fully enjoy either as a result of the other. Kitano has always practised strong critical distanciation in all of his work, using awkward editing, stiff framing, and deadpan actors. Now, he explores this through the more natural means of comedy and music in his work. In truth, Kitano has really changed little or his earlier formula; Zatoichi is far less whimsical or sentimental than Dolls or Kikujiro, it holds far more in common with his earlier yakuzaeiga; the taciturn loner , crime, gangwars and extreme violence all feature.

The final sequence challenges our relationship to the film.

The original director, Kenji Misumi took heavily from Kurosawa’s great films to try and emulate the jidaigeki feel of his work, however he does not problematize audience, and uses kitschi iconography to force the audience’s empathy with Katsu’s Zatoichi.

Karatsu notes how “Kurosawa’s jidaigeki comedies restrain their kitsch elements by means of laughter.” However, Kitano takes these elements of comedy, and does not use them in a realist manner. As such, Kitano’s Zatoichi reduces the world of the film to symbolic. Kitano never allows the audience get too close to his Zatoichi through a variety of techniques.

“In contrast to Kurosawa’s realistic and authentic jidaigeki comedies, the constant reminder that we are indeed watching artifice punctuates Kitano’s Zatoichi.” (Karatsu) It is also is the most knowingly artificial of the three and he de-fetishises the franchise as a result. Kitano has struck the perfect balance between preservation and rejuvenation.His Zatoichi is more focused, less directly sentimental. Every time before that Kitano has explicitly courted Japan with his cinema, he has been rejected. Why is Zatoichi different? Apparently, Kitano needs a foil over his work before Japan will take it seriously; a separator between actual Kitano films and otherwise. Zatoichi enters into a critical discussion with Kurosawa’s jidaigeki’s and the original Zatoichi franchise while also retaining Kitano’s style and feel.

Work Cited:

Karatsu, Rie. “Nihon Cine Art: Between Comedy and Kitsch: Kitano’s Zatoichi and Kurosawa’s Traditions of “Jidaigeki” Comedies.” Nihon Cine Art: Between Comedy and Kitsch: Kitano’s Zatoichi and Kurosawa’s Traditions of “Jidaigeki” Comedies. N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Apr. 2013.

Mes, Tom. “Midnight Eye- Takeshi Kitano.” Midnight Eye – Visions of Japanese Cinema – Interviews, Features, Film Reviews, Book Reviews, Calendar of Events, Links and More… N.p., n.d. Web. 02 Apr. 2013.