With Hana-bi, Kitano’s work begins to slough off its hardcore tough-guy skin—and the ascetic style associated with it—and find an international arthouse audience. (Bob Davis)

In this retrospective, Hana-bi(1997) is probably Kitano’s most significant so far in his career. Winner of the 1997 Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival and the Grand Prix of the Belgian Syndicate of Cinema Critics, Hana-bi put Kitano firmly in the world festival and critical circles as a director worth watching. From a technical standpoint, it is his most accomplished work yet. The distanciation of Violent Cop(1989) has been transmuted into sympathy and emotion, the visual fidelity toyed with in Kids Return(1996) and Sonatine(1993) has gone from plain to painterly. The editing flows in a way most people have never seen before. His aesthetic is entirely his own, or so it seems. There are strong links between his film work, and that of celebrated modernist Japanese director Yasujirō Ozu, links that are more apparent in this, Kitano’s most successful work yet. We have Kitano operating on a level of technical, fragmented brilliance in Hana-bi that the 6 films prior all build towards.

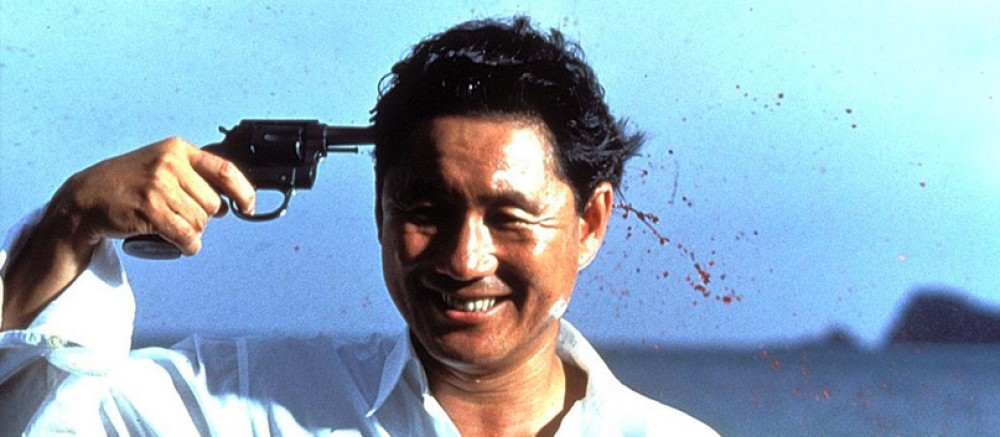

Gentle comedy sits aside teeth gritting violence in Hana-bi

The plot has essentially two main thrusts, the stories of Nishi and Horibe, two retired policemen trying to find meaning in their lives. Nishi’s wife is dying, and he is mired in debts to the yakuza, while suffering guilt over the deaths of men under his command and the paralysis of his partner Horibe whose wife and child leave him after a stakeout gone awry. The plot is, as Kitano standard, nothing special, however it’s presentation is what has it’s beguiling effect. “Whilst the narrative of Hana-bi is essentially classical, it is delivered in a spatially fractured, dislocated fashion. Kitano reveals elements of his story like puzzle pieces, disclosing information in dislocated flashbacks, forcing us to reorient ourselves within the narrative, as we do after the elision of key scenes in Ozu’s films.” (Freeman)

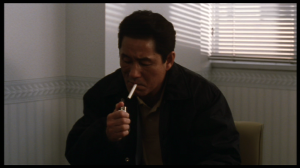

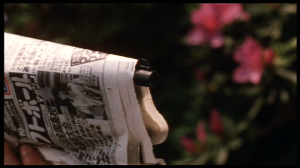

Hana-bi, is both new and old, a hybrid of filmic styles and techniques, borrowed from Ozu and otherwise. The modernist narrative touches of Ozu are used, combined with some some extremely hard edits to both lull and stun the audience. When Kitano’s character, Nishi, light’s a cigarette in the meditative hospital, the film cuts to a gun going off and Horibe falling over, blood on his stomach. The two scenes are repeatedly intercut after this, action and inaction blended into a hybrid style. flashback is interwoven into the plot backwards, we see bodies on the floor from which bullets explode outwards of, and other glimpses of the flashback prove to confuse us as to past events until we finally get the right order of things. Only Kitano can so gracefully move from moments of serenity to violence, a technique long practised at this stage.

An example of the atypical editing present in Hana-bi. The long take of Kitano lighting his cigarette explodes. Silence punctuated by violence.

Ozu is a modernist who built his scenes around unconventional, fragmented editing. He is famously known for his narrative ellipsis, for example in Late Spring(1949), Ozu does not show us Norikio meeting her husband Satake. Instead by leaving these key scenes out, one has to fill in the details and interpret what is going on actively. We are not shown Horibe’s family leaving him, or why Nishi took out a yakuza loan, Kitano removes the excesses so that we can focus on the essentials of the moment.

A key aspect of Hana-bi’s style is it’s stillness, taken from such directors as Ozu. Late Spring(1949) contains a scene in which two fathers converse, and their appearances are akin to the rocks in the rock garden they sit at, they move so little. The camera and stiff editing allow us to make the allusion ourselves.

Hana-bi takes his stillness and combines it with the action and violence of a more contemporary plot. “Kitano’s film reflects much of the Ozu tradition, yet blends his use of narrative space with contemporary approaches to action and movement.” (Freeman) In the opening sequence, our establishing shot comes late, behind the action. We get a shot of the sky, two men staring blankly, and then what we can assume to be a reaction shot from Kitano, a cut of rubbish on a car, we then get an extreme long shot that tells us little, and then a quick cut that reveals that Kitano is standing closer to the two men than we think, the sound of a punch, and then a rag washing the car. The filmic process has been stripped down to impulses, actions are things we have to construct ourselves. Nishi barely says a word in every scene he is in, contained within the shot silently. “Nishi’s face, obscured by dark glasses and frozen in an impassive expression, typifies the void of Ozu.” (Freeman)

The opening sequence as described above:

This stillness extends into the main characters, who have in effect stopped living. They pause and dwell in silence, not expressing what they think. When your actors become still images, some transmutable power is expressed, and Bob Davis describes how the audience puts their own contexts onto the imagery, “Each movie becomes, then, one long Kuleshov experiment. Nishi’s stillness is similar to photography, a medium far more open to interpretation than film. “His(Kitano)hypnotic inertia creates a subjectivity alienated from the audience, generating an unsettling ‘otherness’ on screen. The sense of distance this produces allows non-fictional elements to enter our experience of the image, opening Kitano’s presence on screen to an affect normally associated with still pictures.” (Edwards) Horibe is an extremely sympathetic character, a man having lost everything, who tries painting to fill the emptiness of his days. In a powerful scene, he contemplates flowers, which then cut to the painting presumably in his head. The imagery is lush, and Kitano suggests the state of inspiration effortlessly.

While the violence and thematic content of Hana-bi is modern, the style takes from Ozu and Freeman notes that “Kitano’s power lies in his ability to unite these two worlds, these opposing forces that rely so heavily upon each other. (Freeman) Hana-bi, marks a diverging point in Kitano’s films despite having all of his original hallmarks.

Works Cited

“Cinespot : A Great Auteur – Yasujiro Ozu.” Cinespot : A Great Auteur – Yasujiro Ozu. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Davis, Bob. “Takeshi Kitano.” Senses of Cinema RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Edwards, Dan. “Never Yielding Entirely into Art: Performance and Self-Obsession in Takeshi Kitanoâ s Hana-Bi.” Senses of Cinema RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Freeman, Mark. “Kitanoâ s Hana-bi and the Spatial Traditions of Yasujiro Ozu.” Senses of Cinema RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. “Is Ozu Slow?” Senses of Cinema RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Wrigley, Nick. “Yasujiro Ozu.” Senses of Cinema RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.