“But the more you show tragedy, the more you have to go in another direction after, like the swing of the pendulum. And here, I wanted to show something tender and funny with the same force that I had shown violence and sorrow.” (Kitano in discussion with NY Times)

Completed after Kitano’s greatest critical success abroad, Kikujiro (1999) is a puzzling film for western audiences becoming familiar with Kitano. An outright comedy, and a return to his TV roots just after his most successful film, Hanabi(1997). It sits in a strange place in his filmic canon. Neither ribald enough to match Getting Any(1995), or noble enough to sit alongside Hanabi, Kikujiro has to fend for itself on both sides of the world. A retired, ex-yakuza, Kikujiro, is tasked by his wife with taking a small boy, Masaru, to find his mother. However, Kikujiro, by virtue of his slovenly character transforms the simple situation into an absurdist road movie, as he spends his travel money on gambling and has to take them across Japan as cheaply as possible.

However, the film defies categorization in a manner fitting Kitano’s life mission statement; that nobody should be able to predict his next move. For those familiar with his refusal to be pigeon holed, it is an apt film.

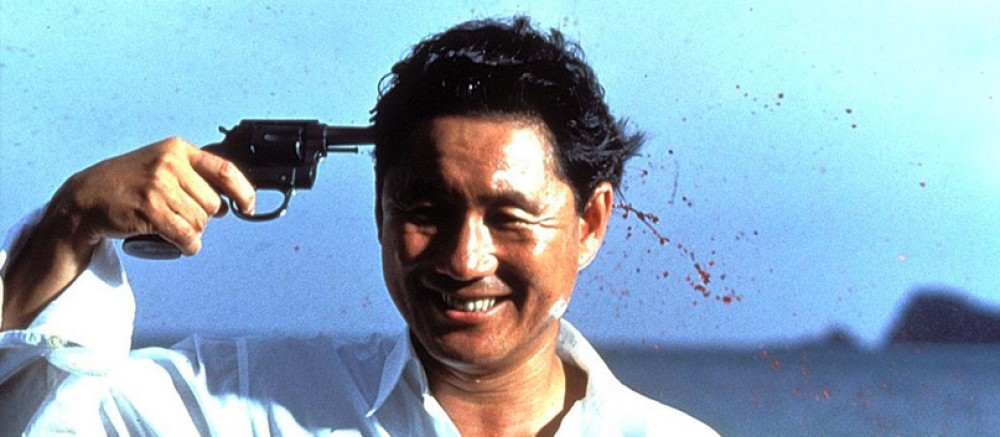

Kitano takes iconic props from his earlier work, and plays them for laughs.

Instead of a minimalist loner’s journey, we instead get a comic romp. Structurally, the film centres on a series of escapades that the two have, as filtered through Masaru’s journal in a send up of the classic “What did I do last Summer?” school assignment. and the characters they meet that help them in various ways, as they make it to Masaru’s mother’s house and back. Again, the plot is simple, but it is the layers of intertextual reference made to Kitano’s life, other films and TV work that define and complicate the patina presented to us. This film complicates Kitano, and his relationship to both of his audiences in several ways. Most notably through the figure of Kikujiro himself. Kikujiro, Kitano explains to numerous interviewers, is his father’s name, and is based on him and numerous other men Kitano knew growing up in a less than genteel part of Japan. “Born in Tokyo, he spent his childhood in the poor neighborhood of Asakusa… “When I was growing up, I hardly knew him. He gambled and drank, was either absent or violent. I was the youngest of four, and he terrified me. But when I became a father myself, I reflected on this solitary and sad man and tried to invent a relationship with him.” (Dupont Kitano NY Times)

Kikujiro amongst other things, cannot swim.

Kikujiro is a yakuza to some extent, a trait shared between many of Kitano’s previous characters, and he likes to wear sunglasses like Nishi from Hanabi. Confusing audiences further, Kitano problematizes the difference between the taciturn tough guy persona of his Kitano films, and the buffoon figure of Kitano’s TV alter ego, Beat Takeshi, by blending them into Kikujiro. Kikujiro is a loud-mouth, berating Japan, and Japanese stereotypes whenever he meets them, and as a failed yakuza, is rather pathetic in some ways, and is totally different to the domineering Kitano personality of his previous films. Kikujiro only sometimes gets what he wants.

There are numerous references to Kitano’s alter ego Beat Takeshi, and his work in the film, not least the extended scenes of play where Kikujiro and his new friends, the bikers, and the traveller try to cheer up Masaru.

However, the bikers are actually gudan, a part of Beat’s loyal followers on TV shows such as Takeshi’s Castle, the popular game show, and as such, they are strangely compliant with Kikujiro’s bullying and demands. Underlying ripples of behaviour such as these, and the games that the group play are all extremely referential to Beat Takeshi’s cult of personality in Japan. This is reinforced through Kikujiro’s behaviour. Kikujiro himself is neither the silent tough guy or the buffoon But a flawed character, having more in common with a clown than other Kitano characters of the past, and even flirts with tap dancing, something Kitano himself practised.

There is a nuance and parallel comparison going on in the film between Kitano, Kikujiro, family and the child Masaru, one that Japanese audiences might have been more receptive to, Kitano’s autobiographies often being turned into soap opera dramas, but apparently they miss the nuance. In one interview, Kitano baits the two audiences he has against each other.

Moments of quiet introspection punctuate the film aside the comedy.

“When a Japanese audience Watches this film, Kikujiro, they see the TV comedian Takeshi and that’s all. They stop short of going into the emotions. They don’t try to read the inner feelings. On the other hand, the Cannes audience is unfamiliar with me as a comedian. They see me as just one of the characters. They make an effort to read inside the character. As far as Kikujiro goes, the reaction in France was far better.” (Kitano on Sbs film)

How much of Kikujiro himself is fictitious or real? It is difficult to know. Kikujiro is framed through a child’s scrap book of memories, and as such, Kitano could in fact be in the place of Masaru in the film. Kitano describes how he feels Cannes’ audiences can appreciate his filmic work far more than Japanese audiences, and yet in Kikujiro, he references Beat Takeshi’s brand of humour in numerous ways. We are in a strange dilemma then, as Kitano loads the film with references to his extremely Japanese comedic life, that a western audience could not get. Kitano makes reference and gentle fun at other aspects of his life, TV career and filmography through the character Kikujiro and through the characters he meets.

Tommy Udo writes of how it is “the director’s most autobiographical movie to date, Kikujiro could be seen as a key to all of his work. Kitano’s own father, a largely absent drunk also named Kikujiro, was once forced to spend a summer with his son, much like the character Kikujiro with the parentless boy Masao here. However, it would be unwise to read too much autobiography into a work by such a notoriously unreliable and media-savvy narrator, especially one that feels lighter and less personal in tone than Hana-Bi.”

Kitano is the master of two personas, and of two audiences.

Works Cited

“Interview with Takeshi Kitano.” Interview. SBS. N.p., n.d. Web. <http://www.sbs.com.au/films/video/11698243984/interview-with-takeshi-kitano>.

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. “Is Ozu Slow?” Senses of Cinema RSS. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 Mar. 2013.

Udo, Tommy. “Kikujiro.” Rev. of Kikujiro. BFI Sight and Sound n.d.: n. pag. BFI. Web.