At the end when the two friends meet up again for the first time in two or three years, Masaru asks Shinji if he thinks that they’re washed up. I asked myself the same question when I had the motorcycle accident in August 1994. (Kitano in conversation with Rayns)

Kids Return(1996) sits awkwardly at first amongst the rest of Kitano’s output up to this point in his career. He does not feature in the film personally, and it contains little of his now traditional iconography. As such, it is often overlooked when it comes to any film criticism; there are little to no articles written about this film despite the crucial role I feel it plays in the development and maturation of his style. It is a film that is far more personal for Kitano than many in the west may realize, being created just after a tumultuous event in his life. In between Getting Any? (1994) and Kids Return, Kitano was in a horrific motorcycle accident that he referred to as an “unconscious suicide attempt” (Kitano quoted in Lee Server, Asian Pop Cinema)

Kitano himself confesses that Getting Any? was an expression of a self destructive impulse, with which he shattered his auteurist identity in the west and made fun of his own Beat Takeshi humour. Getting Any? appears to be an expression of his internal turmoil that culminated in his accident. Kids Return is a film made almost as personal proof that Kitano could still enjoy the act of creativity after the accident, and to take a re constructionist approach to his cinema. He strips his tropes down, and centres the film not around adults, but around a small group of high-school boys who are trying to find meaning in their lives outside of education. Masaru and Shinji meet at the start of the film three years after they last met, having tried and failed to make something out of themselves. They reminisce together on their high school years, their triumphs and failures. Gone are the deadpan long takes, the unconventional editing and structures, a heavy presence of crime film tropes, and everything else Kitano is known for, is replaced with is a clear purity shared with A Scene at the Sea(1991).

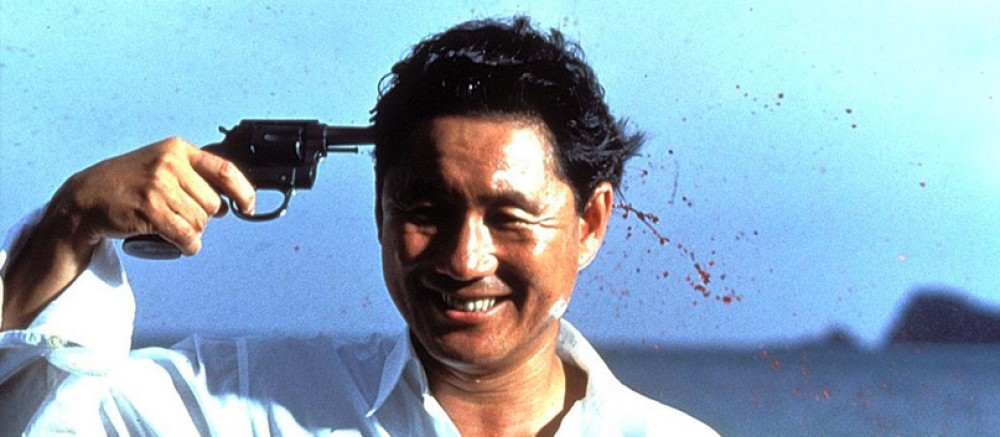

Here, Kitano takes liberally from his own childhood; the two boys are not suited to the class room and to traditional jobs. They dabble in stand up comedy, and attempt amatuer boxing before the best friends are divided by their choices; Masaru joins the yakuza while Shinji remains a boxer. Not a single role works out for them. As such, the film also explores dismissive patriarchal relationships between the boys and their teachers in the gym, work and at school. Each time, the misguided delinquents are let down or misguided as such by an older father figure. Ultimately both boys make errors of judgement and their chosen avenues close on them, they separate until meeting at the start of the film. They do not die, only make mistakes and learn, in much the way that Kitano himself did. “The earlier films are about finding the right way to die. These characters have to live; they’re the way they are because of the state I was in after the accident.” (Kitano talking with Rayns)

The aesthetic of this film is part of an overall trend in Kitano’s later films for aesthetic purity. Colours are implemented more consistently than any other of his films up to this point, Violent Cop (1989) is positively crude by comparison. Masaru is identified with red while Shinji with blue, a direct way of communicating their personalities, and how complementary the two characters are. The shots and formal structure of this film make it by far the most typical mainstream film in appearance that Kitano has made at this point. Though, despite this accessible exterior, the internal mechanics of the film are probing truths about Kitano himself and about live in Japan for youths that make mistakes. Kitano himself finds the film to be an explicit relation to his situation post the accident.

“At the end when the two friends meet up again for the first time in two or three years, Masaru asks Shinji if he thinks that they’re washed up. I asked myself the same question when I had the motorcycle accident in August 1994. 60-70 per cent of me thought that I was through, that I couldn’t go on. But the rest of me thought that I’d hardly begun. I don’t know if Shinji and Masaru will go on to achieve anything or not, but it’s certain their past mistakes and failures will make it very hard for them, especially in Japanese society.” (Kitano in conversation with Rayns)

Kitano’s characters ask themselves if life is over that quickly, and with the final lines of the film, it seems that Kitano has the answer.

Do you think we’re already finished?

No way. We haven’t even started.

Works Cited

Lee Server, Asian Pop Cinema, op. cit., p. 82

Rayns, Tony “The Harder Way.” Welcome to Kitano Takeshi . Com. N.p., n.d. Web. 12 Feb. 2013.