The great enemy of documentary (and oddly, rather a taboo topic of discussion among film- makers themselves) is the “dead spot” in which nothing seems to be happening. Film producers are terrified of such moments, for they are terrified of audience impatience. (Mac Dougal 38)

This fear of the ‘dead spot’ also applies to narrative cinema, and in his second film, the great farce, Boiling Point (1990), Kitano embraces this fear. Characters stare at each other and stare at the camera, in shots up to twenty seconds in length, as time balloons past simply feeling slow and becomes glacial for modern audiences.

The question is indeed, why is Boiling Point the way it is. In this film, we can still see Kitano still finding his filmic style. His characterization falls flat, but the eye for style, for the absurd, and his pacing all call towards his later masterpieces such as Sonatine and Hanabi. Boiling Point concerns itself with the bumbling Masahiko, whose life has no direction. He idiotically lashes out against a bullying yakuza member and the yakuza start pressuring his garage work place. His baseball coach, Iguchi, an ex yakuza, intervenes and gets hospitalized. Masahiko and his equally maladroit friend then travel to Okinawa where they ‘befriend’ a gangster Uehara, Kitano himself, who helps them get the guns they want.Compared to other films from the late 80s/ early 90s, Boiling Point is a study in simultaneous restraint and excess. We can place Kitano and his style as at odds with the modern Hollywood trends towards briefer shots with more intercutting, and relate him to an older Hollywood where shots were longer and less claustrophobic. Bordwell distinguishes between the two periods of Hollywood in terms of the post 60’s intensified continuity, writing how the sheer number of shots and edits doubled or more. “At the close of the 1980s, many films boasted 1500 shots or more. There soon followed movies containing 2000-3000 shots… By century’s end, the 3000-4000 shot movie had arrived… Many average shot lengths became astonishingly low. (Bordwell 17)

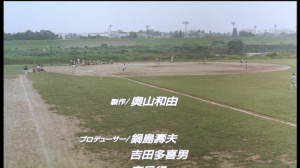

During this period of decreasing ASL, Boiling Point strolls in the opposite direction.For a film about a pending violent confrontation, Boiling Point does not try to remind you of this. Instead, Kitano emphasises the pace of the small city/ rural life in Japan under the sweltering heat, where anger festers under a long slow boil until it’s explosive ending. Boiling Point’space is extremely deliberate. As our introduction to Masahiko, he stares at the camera for 20 seconds, as his introduction to the film. After opening the toilet door, He walks towards the camera for 25 seconds before the third edit, which is a reverse shot of the the second shot which also last 25 seconds. This habit is one that holds for the entire film.Other shots push a minute, others 2 or 3.Directors, editors and TV producers have helped enforce this trend of the faster and faster shots, and we as an audience have supported it. Kitano bucks this trend and probes what emotion he can elicit despite this difficulty of an audience that is trained in a wholly different school of cinema and have issues of empathising with the long take as a result. “Editors tend to cut at every line and insert more reaction shots than we would find in the period 1930- 1960. “(Borwell 17) Kitano balances out the long takes by often punctuating them with brutal violence, or dark comedy.

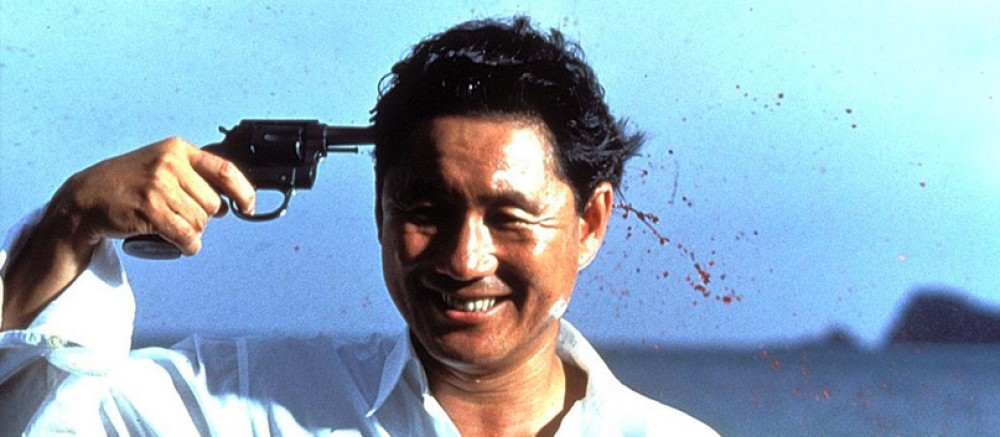

The shot where Iguchi intimidates a yakuza by making him repeat the same sentence over and over until he brutally kills him, lasts for a full minute, however it is magnetizing rather than boring due to the subject matter and potential for violence. Kitano almost raises the question himself, of whether or not his cinema needs violence, when during the two and a half minute long take where Uehara and his new friends relax in the bar. The camera drunkenly staggers from subject to subject as two yakuza wander in and attack Uehara. The kareoke in the corner of the room does not stop, highlighting how surreal the whole comic scene is.

“The mannerism of today’s cinema would seem to ask its spectators to take a high degree of narrational overtness for granted, … The triumph of in- tensified continuity reminds us that as styles change, so do viewing skills.” (Bordwell 25)

In Boiling Point Kitano manages to wrestle our attention in spite of himself with moments of dark comedy. As a result of what he calls modern cinema’s ‘intensified continuity’, Bordwell states how “intensified continuity has endowed films with quite overt narration (25) , The audience is directed to only what the director wants them to see, and have become more passive then past film goers as a result. Boiling Point avoids this overt narration, not directing your eye towards the obvious. A clear example is when Uehara and his subordinate attack the yakuza they have a vendetta with, the editing is fragmented, as awkward pauses between the first accidental spray of bullets and the next pad the scene. In Boiling Point, intensified continuity is attacked, via the unconventional editing. There is a jump cut of Uehara’s subordinate sitting at the yakuza desk, to one of Uehara raping the tea attendant parallel to the desk. The camera never tells us how to feel about Uehara, we can only react to his actions.

However, the final long take of the film, the last shot indeed problematizes a reading of Boiling Point as simple violence bait. Kitano appears to be reaching for some thematic depth that he does not quite reach. The final shot of the film is a reference back to the 3rd 30 second shot in the opening, as Masahiko jogs rather than walks back to his teams side after awaking from his daydream in the toilet. However this shot lasts for over three minutes, and the credits begin to roll over it. The long take that challenges narrative closure triumphs over traditional audience direction. We stare a little longer and harder at this one.

Works Cited

Bordwell, David. “Intensified Continuity Visual Style in Contemporary American Film.” Film Quarterly 55.3 (2002): 16-28. JSTOR. Web.

MacDougall, David. “When Less Is Less: The Long Take in Documentary.” Film Quarterly 42.2 (1992/1993): 36-46. Print.

Pasolini, Pier Paulo. “Observations on the Long Take.” October 13 (1980): n. pag. JSTOR. Web.