Warning: This is a (vaguely) academic write up, Absolute Spoilers follow, Do yourself a favour and watch the film:

“The overwhelming historical presence of violence in folklore, mythical legends, nursery rhymes, lullabies, literature, theatre and film suggests that violence which is experienced receptively through a dramatized medium has some kind of allure.” (Shaw 131)

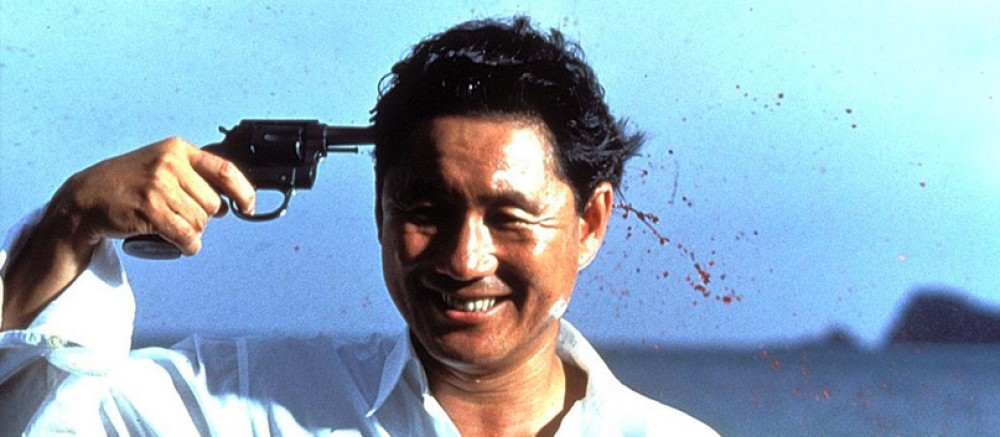

Violent Cop is an extremely intense film. Death follows Takeshi Kitano’s policeman Azuma as he delivers his own brand of justice befitting the title. Despite the horrific content, it never loses sight of its thematic content, with Kitano filming the violence with a dispassionate eye. Why is Violent Cop the way it is? Kitano’s directorial debut, and one he stars in, contains both innocence and maturity.

Kitano intentionally or otherwise, attacks the allure of violence in a dramatic context. Azuma’s powertrip is in the beginning almost sympathetic, as he berates and beats a youth who harassed a homeless man, but quickly we see that he has a tendency to go too far. A large part of how we react to the film, is how the violence is depicted. Kitano does not glorify violence, instead showing it to us in a realist fashion. “Violent Cop projects its internal calm through a use of static camera and long and extreme -long- shots that engender an aesthetic of mild distanciation: a stylistic trait which has become a Kitano hallmark.” (Totaro 132)

The film repeatedly makes use of long takes, as Azuma crosses the street, walks up steps or does anything. This grounds us not in the western cinema of emotion, but rather the eastern. As such, western audiences might be challenged by some of the vintage shot composition on display. “If the Western audience perceived emotion through intimacy with a face, the Japanese perceived it through forms set in their environment, seen through long shots, long takes and their pathetic fallacy.” (Richie 12)

Rachel Shaw’s experiment for the University of Leicester shows us that we find violence in films bearable and enjoyable if we can justify it through the plot. “Previously we saw how important the plot was to understanding violent scenes in films; this account reveals an equivalent need for contextualization in real life.” (142)

However, much of our protagonists actions are not tied to the overarching plot. That becomes more pertinent in the latter half of the film. Violence in this film exists for and of itself. Tangential violent encounters are dragged out beyond traditional plot structures. The violence flows in episodes, without consequence. Azuma did not have to kick the abusive partner in the face while he was down, nor did he have to run over the violent criminal. His character is not ever given proper context, he just is.

The aesthetic of the film is always extremely calm and measured, with long takes, and a lack of emotive close ups. There is a strangely leisurely, detached feeling as Azuma and the rookie chase after the man who just smashed open another cop’s head in. Some slow motion is used, and we wince as the baseball bat comes down on a policeman’s head. Another distancer for us Western audiences is that we not used to the vengeful Ronin trope that is layered under the cliches of the yakuza crime film here. “One of the overriding themes of Kitano’s directorial debut is the blurring of the worlds of law and crime, cop and criminal.” (Totaro 133) The violence cannot be justified by the plot but it stems from a Japanese narrative trope. Azuma becomes embroiled in a vicious cycle of violence with the Mob boss’ best hitman. However, the characters bear far more in common with Samurai, and the dualized leads both become shamed ronin, having lost their idealized position and care not for death as they hunt and pursue each other. The worlds of beauty, peace and of hatred are also blurred, as Azuma’s single solace in caring for his sister is ultimately taken from him. Violence also crosses boundaries, when one of Azuma’s bullets is deflected and hits an innocent girl. Neither Azuma or his rival care.

Identity is portrayed as fluid. The iconic long shot of Azuma walking across the bridge towards the camera is recreated at the end of the film by his rookie partner. This implies that he will follow in Azuma’s steps, but rather he becomes more like the corrupt cop Iwaka who was working with the drug ring the entire time. Morality is fluid, appearance is also, and loyalties more so; the sweet nervous rookie will become a cold man. The lawmaker can be a tyrant.

We can see that Violent Cop would have been a very different film if it were made by any other culture or by any other man. It is laden with cliches from a character perspective, but it is the tight reign of control that Kitano holds, and the treatments of these cliches under his meditative eye that reveals some primal truth in them.

Works Cited

Richie, Donald. Japanese Cinema: An Introduction. Hong Kong: Oxford UP, 1990. Print.

Shaw, Rachel Louise. “Making Sense of Violence: A Study of Narrative Meaning.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 1.2 (2004): 131-51. Web.

Totaro, Donato. “Sono Otoko, Kyobi Ni Tsuki Violent Cop.” The Cinema of Japan & Korea. London: Wallflower, 2004. N. pag. Print.