“There sheer idiosyncrasy of the film bespeaks the singularity of the position Kitano has carved for himself as a director…He makes the best he’s able to of each project that comes his way, greeting successes with self-deprecatory modesty and shrugging off failures while gearing up for the next one.” (Rayns)

Tony Rayns wrote the above as part of a film review for Dolls (2002), Kitano’s strangest film yet. Rayns perfectly describes the attitude that Kitano has towards building anything like a coherent legacy. Each project Kitano directs is extremely different; the structural and editorial hallmarks are there, but the thematic and subject matter diversity, having moved on from crime movies, gives him total freedom as a director. Kitano does one thing for a period of time, and then doubles back and does the other. Perhaps we can view Dolls (2002) as an attempt, fitting of his erratic work habits, to claim back the Japanese audience after his attempts at wooing film festivals so overtly with Hana-bi and Kikujiro.

Kitano resists the use of (most) of his character tropes in Dolls. We certainly have never had a company man, popstar or blind rabid pop fan be the main characters in his films before. Typically the characters stem from binary sets; yakuza or cop, though we still have the yakuza in the ranks here.

The film is his most visually rich yet, with the main character’s clothes designed by a fashion designer- and as such, are totally out of step with anything resembling practicality. There is an emphasis on colour and composition that Kitano has only hinted at in his earlier work. A key part of the visual makeup of the film is his use of Japanese culture. Each of his films utilizes Japanese culture tovarying amounts. Hana-bi(1997) has been criticized by Darrell William Davis as a cynical cultural tourism, designed to appeal to foreigners with it’s flavour of the month orientalism. Writing about the imagery in Hana-bi he said : “In spite of their ostensible innocence, as if discovered by orphans or foreigners,these objects are “cheapshots,”exploitations of stock images. (Davis 73)

But Kikujiro (1999) , which Kitano claimed the most receptive of his films to western audiences, contained far more Japanese iconography than Hana-bi, with it’s lampooning of various tropes and TV shows that Kitano himself runs. Davis’ assessment for Hana-bi can be seen as sound, but what does it say about his other films? It is clear that Kitano has an extremely complex relation to issues of national identity from his earlier work. So where does Dolls fit into this, his most dense, in this regard, film yet? Kitano based the concept and the artificiality of the film on the work of Chikamatsu Monzaemon, who crafted theatre shows with doll actors that needed three operators per doll. After an opening demonstration of the powerful bond that the two dolls share, the dolls become the audience and puppeteer of reality, and three vignettes play out as the the Japanese theatre bunraku aesthetic takes over these lives. A couple are symbolically rendered unto the literal dolls, and wander silently together, meeting the other characters in various ways.

In true Kitano fashion, each of the plots are doomed, though they are now more tragic than ever as he infuses sentimentality into each one. Kitano blends life with traditional Japanese theatre in a visually artificial way. How do film and culture interact? Kitano is almost making it too explicit. “Studies of national cinema- and english-language Japanese cinema studies are exemplary-have not paid enough attention to this complexity, assuming Japanese culture was “there” to be “taken” by cameramen and performers.” (Davis 61) At least Kitano challenges this somewhat. He ramps up the amount of Japanese “culture” massively in Dolls, and mixes it with his own aesthetic in a way that challenges this idea of Japanese culture as inherent in everything that Japanese people do. The film is so artificial and at times, forced and gaudy, that one would be hard pressed to watch it and say, That is Japan.

Though the magical reality of the living dolls sits uneasily with the other more grounded stories; that are equal parts daytime soap and newspaper fodder. As such, Kitano makes no pretence at all that the film makes any claims about Japan.“Far from representing a nation or a region, a filmmaker like Kitano wants to be known as an auteur who breaks out of the constraints of national cinema. But how? Kitano shrewdly inserts himself into an unorthodox, atypical nationality that suits the transcultural forms international festivals celebrate. (57 Davis) Kitano instead in interviews appeals to personal anecdotes as a means to justify his fascination with one aspect of Japanese culture and in Dolls allows it to grow into a hybrid with his own style.

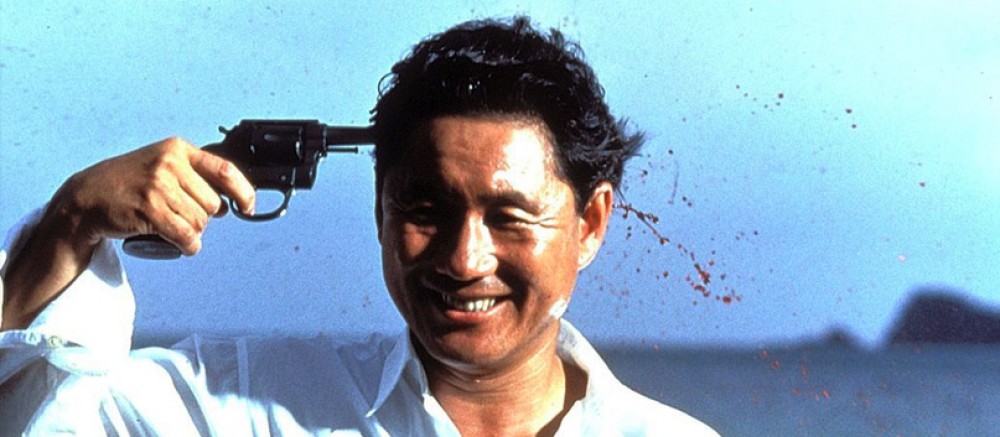

Kitano understands this need of films of the stereotypes of other Japanese media to allow itself to be contextualized. It can be said of Kitano to some extent that he liberally drizzles direct Japanese iconography into his films that western audiences would not understand- despite to this point being his biggest audience- to contribute to the cultural tourism effect that he takes advantage of as a director. In Hana-bi, his greatest success, the references are relatively subtle compared to the arch use of Japanese iconography in Dolls. He blends Japanese tradition with contemporary Japanese fiction tropes to purport that the ideas of love hasn’t changed all that much from generation to generation. The tension between various aspects of the film is strange, and it at times feels like it bursting at the seams. Kitano now blends the worlds of film and theatre together, he applies his touch to a new genre for him, that of romance, and increases his visual fidelity. Each of the three romances is doomed, and would be rendered as generic if only based on the plot content. However, Kitano’s minimalist mise-en-scene, and touches such as the long take can be seen as rather akin to theatre for a short spell, though that is a form that Kitano is not that far removed from. Dolls is Kitano’s most artificial film to date, magical realist film, one that still is undeniably one of his films, with all of its’ hybridity and with strong ties to theatre.

Works Cited:

“Dolls – An Interview With Takeshi Kitano.” Dolls – An Interview With Takeshi Kitano. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

Rayns, Tony. “BFI – Puppet Love.” BFI. N.p., n.d. Web. 26 Mar. 2013.

Davis, Darrell William. “Reigniting Japanese Tradition with Hana-Bi.” Cinema Journal 40.4 (2001): 55-80. Print.