“It is thus absolutely necessary to die, because while living we lack meaning… Death performs a lightning- quick montage on our lives; that is, it chooses our truly significant moments (no longer changeable by other possible contrary or incoherent moments) and places them in sequence… It is thanks to death that our lives become expressive. Montage thus accomplishes for the material of film (constituted of fragments, the longest or the shortest, of as many long takes as there are subjectivities) what death accomplishes for life.”

(Pasolini 6)

A Scene by the Sea (1991), seems at first, to be a film very far removed from typical Kitano conventions. It features no violence and no yakuza. However, it still manages to be uniquely a Kitano film. What is unique tohis films apart from the more obviously iconic ingredients? Kitano keeps up the experimenting spirit of his prior film Boiling Point in several ways; this film is a development of the more subtle aspects of his work- such as how how little dialogue he needed to maintain a scene. Kitano during his first three films, seems to be always probing towards the films he wanted to make.

From a technical aspect, A Scene by the Sea offers a unique challenge as part of these three. The incredibly sparse dialogue, long takes, simple characters, and incidental plot all combine thanks to Kitano’s alchemic thematic considerations to become more as a grand sum.

A Scene by the Sea concerns itself with Shigeru, a deaf garbage collector who finds a broken surfboard one morning at work, repairs it, and with the support of his also deaf girlfriend Takako begins to surf. Very quickly it becomes a consuming passion of his life and other parts of his life start to suffer while he develops his talents.

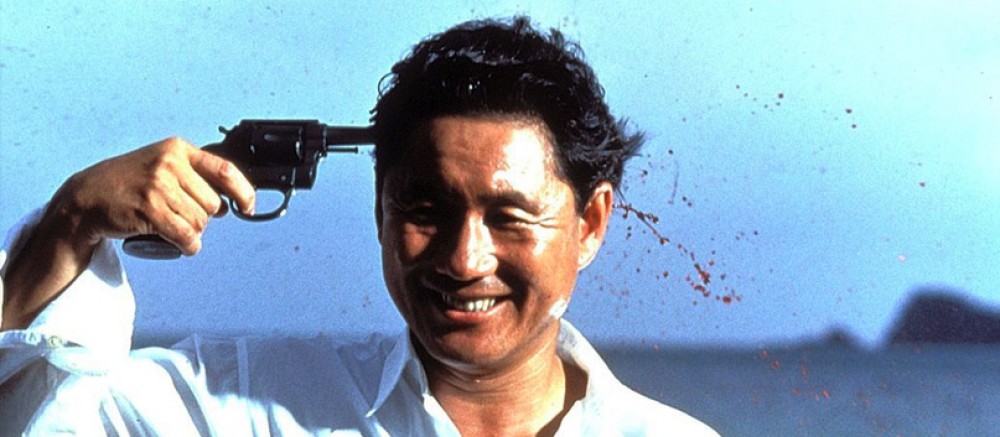

Repeatedly, Kitano characters die at the end of his films, on the cusp of happiness, or success in their goals. A Scene by the Sea is no different. Shigeru’s board is found by Takako one stormy morning after his talents have developed meteorically and he has taken home a trophy for his talents. Such a sudden ending for our main character leaves a sour taste in the mouth. This trend of tragic death in Kitano’s work linked to the asian philosophy of mono no aware, itself stemming from Buddhist thought. Mono no aware is far removed from western audiences know and what they expect from cinema. It translates to “The pathos of things”. To fully celebrate one’s life or any subject, one must understand the essential transience of this universe and everything in it. For the Japanese mind, the world is in flux and everything dies. Rather than simply lament at this, the world and everything in it is more beautiful for it. In Japan, Cherry Blossom viewings are a major national pastime. They last a week. They blossom and they fall. The beauty in being able to watch something is contextualized by the immanent death of the subject. The Sea, which after Boiling Point, begins to feature greatly in many Kitano films, has been responsible for external influences on Japan, bringing foreigners, new cultures and industry on its waves, and in that respect a large supplier of fuel for modern mono no aware.

We can find mono no aware and the notion of kire, to cut, in A Scene by the Sea. The emotions evoked by Shigeru’s death coupled with his transient successes are cruel, but for mono no aware, necessary. Kire is connected to Japanese flower arranging; the flowers are only truly considered alive when they have been cut. Ikebana means “making flowers live”. This allows the viewer to see Shigeru’s life, and his achievements with greater clarity. Death contextualizes life. There is no triumphant long life to be had for Shigeru; to be cut in his prime allows us to ascribe meaning to his life, in much the same way that Pasolini claims editing gives meaning to filmed footage. Kitano emphasises both concepts by showing us footage of Shigeru and Takako’s life that was not in the film, and various shots of the cast laughing at the camera after his death. This breaking of the verisimilitude of the film, by acknowledging that there is a camera there, shows us of Kitano’s awareness of the meaning that editing imposes onto footage as he becomes an ikebana artist, having edited the film himself.

Mono no aware and kire, can be seen as a plague to Kitano’s characters, or as a thematic enabler. Kitano’s characters being aesthetic ciphers than psychologically realistic beings. Shigeru might not have explicitly died on camera, like Azuma in Violent Cop or Murakawa in Sonatine. However his death is just as emblematic of Kitano’s aesthetic concerns.Through the process of arranging his character’s death, Kitano gives us a chance to look again at the character, instantly re-contextualized. Mono no aware, the dwelling celebratory eye, a particular, slightly painful and loving emotion, aware of coming change and the loss of the stable norm. What more fitting symbol for this than the sea?

Works Cited:

Pasolini, Pier Paulo. “Observations on the Long Take.” October 13 (1980): n. pag. JSTOR. Web.

Parkes, Graham, “Japanese Aesthetics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2011 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/cgi-bin/encyclopedia/archinfo.cgi?entry=japanese-aesthetics/>.