Sonatine(1993) can be seen as the event horizon of Kitano’s previous efforts to combine various aspects of his style into a more coherent whole. Returning to the criminal world of Boiling Point (1990) and the melancholy of A Scene at the Sea(1991), Kitano takes the tropes of the Japanese yakuza film and applies his sensibilities and artistic concerns to a genre that Paul Schrader saw as “probably the most restricted genre yet devised”, composed of “litanies of private argot, subtle body language, obscure codes, elaborate rites, iconographic costumes and tattoos”. (Varese 3) Kitano manages to create something new out of the genre of the Japanese gangster movie, or yakuza-eiga.

Sonatine’s location proved to be extremely effective at differentiating the film from other yakuza-eiga.

Is Sonatine so powerful only because of this culture shock to western audiences? Or was it different enough from other Japanese crime films to be of note? There are clear and strong demarcations that writers have noted between the american gangster films and the yakuza-eiga. We can find a concern with social commentary, and a strong link to noire in american crime cinema, which is contrasted with the yakuza-eiga, and their concerns with identity as part of a group and the personal obligations to codes and honour. Indeed Paul Schrader argued that “The Japanese gangster film aims for a higher purpose than its western counterparts: it seeks to codify a positive workable morality. In American terms it is more like a western than a gangster film. Like the western the yakuza-eiga, chooses timelessness over relevance, myth over realism; it seeks not social commentary but moral truth. Although the average yakuza film is technically inferior to an American or European gangster film, it has achieved a nobility denied it’s counterparts- a nobility normally reserved for westerns.” (Shrader 10)

Sonatine’s extended sequences of the gangster at play, challenge this nobility.

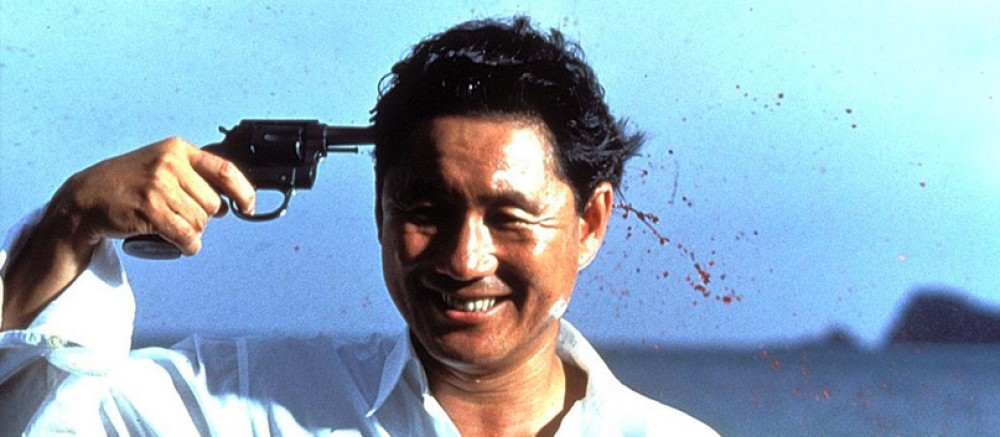

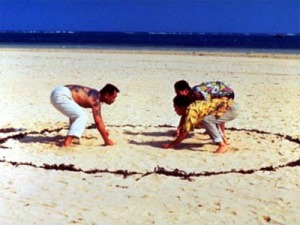

In the character of Murakawa, Kitano finds some semblance of nobility, and then abandons it at the seaside. Murakawa is a veteran yakuza, who tires of the yakuza themes of duty(giri) and humanity (ninjo) that Paul Schrader identifies of as being key components of Toei’s extremely formulaic yakuza-eiga output. Murakawa wants to leave the yakuza, unfortunately he and a small team are asked to mediated between two warring factions out in rural Okinawa, and spend most of the film reliving their youths on the beach as it is the only safe place for them to be. Gangster life is suspended as they dance, throw frisbees and sumo wrestle on the beach until real life eventually comes calling. We find the atmosphere of distanciation first articulated in Violent Cop becoming something more meditative, as his framing and long takes which now concern themselves with the character of Murakawa, a yakuza who challenges norms.

The Toei film company had the most success with the yakuza-eiga and they eventually supplanted period dramas as Japan’s premier audience pull. Production started in the 60s with low budgets and their form became less ritualized and become more in line with cinema verite. “The enormous success of The Godfather in Japan caused the Toei brass to finance more ‘documentary’ style yakuza films.” (Schrader 10). Sonatine has neither the ritualistic fetish-ification of the 60s yakuza-eiga or the documentary leanings of the 70s examples of the genre. The 70s are viewed as the yakuza-eiga golden age, and that “After this brief window of opportunity, the studios reasserted their control on the style and content of yakuza movies, thereby (metaphorically) killing this genre. (Varesen 17)” Sonatine exists during a time when crime movies were only again coming back from the dead as a genre in Japan.

Paul Schrader argues that this difference between American and Japanese productions stems from the historical links that the yakuza-eiga has to the samurai film .American and Japanese crime films are thus very different beasts. Yakuza films at all had died out by the time that Kitano started working, and as such, he has a large history and contextual framework with which enter into discussion with. Kitano and his relations to Japanese gangster films.

However, Sontaine’s idyll is shattered by the bookending plot structure These men are being hunted. They forget this and pay the price.

Paul Schrader describes how formulaic these yakuza-eiga films are, “A typical Toei yakuza film- there’s no use mentioning specific titles since most of Toei’s three hundred or so yakuza films have the same plot structure…” In his write up, he tells that these films were generated in manners similar to the Hollywood systems with scripts written by committee, and films on production lines. Such is the formal structure imposed, that Schrader outlines 20 set pieces that one can expect at least 2 of to appear in any 60s yakuza-eiga film. These include visits to prison and all manner of violent confrontations. However, Sonatine’s plot is a set dressing to the effect of the film. The generic tropes of the yakuza-eiga only feature for the first 15 minutes or so. With the domineering gang head, the Oyabun, having put a noose around Murakawa’s neck with his plotting and against who Murakawa ultimately kills in the final climax. Though for the majority of the film, Sonatine is a crime film drained of narrative impulse. By the time that Murakawa reaches the beach, he is eager to forget his criminal ties and to frolic. However, the overarching plot eventually takes hold and he must finish everything and cut off every tie to the yakuza films of the past by killing every culpable member he can at the shootout. The age of the gangster film is long gone by the 90s and this lack of other traditional, heavily ritualized yakuza film allows Kitano certain freedoms with the narrative and form. Kitano’s films are shot as cheaply quickly as possible, as with his Toei-B movie ancestors, His cultivated style now plays fully into his favour, with extremely striking shot compositions that take full advantage of the sun, sand and sky. It took men outside of Toei, either independent, or with Office Kitano, to give stylistic evolution back to the yakuza-eiga.“Engaging portrayals of the yakuza in the 1990s were produced outside the Japanese studio system by directors such as Kitano Takeshi, Miike Takashi and Sakamoto Junji. The movies of this new generation of filmmakers deal in extreme violence, deadpan wit, and deeply felt human dilemmas. They also portray the yakuza in a less than flattering light, although they do not totally eschew their genre roots: they do shy away from presenting the yakuza as downright buffoons. (Varese 17)” Kitano suggests that what lies under the yakuza veneer is a desire to be a child again, to forget the death wish this lifestyle has placed on their heads.

Works Cited

Schrader, Pail. “Yakuza-Eiga- A Primer.” Film Comment Jan-Feb (1974): 8-17. Web.

Varese, Federico. “The Secret History of Japanese Cinema: The Yakuza Movies.” Global Crime 7.1 (2006): 105-24. University of Oxford. Web.